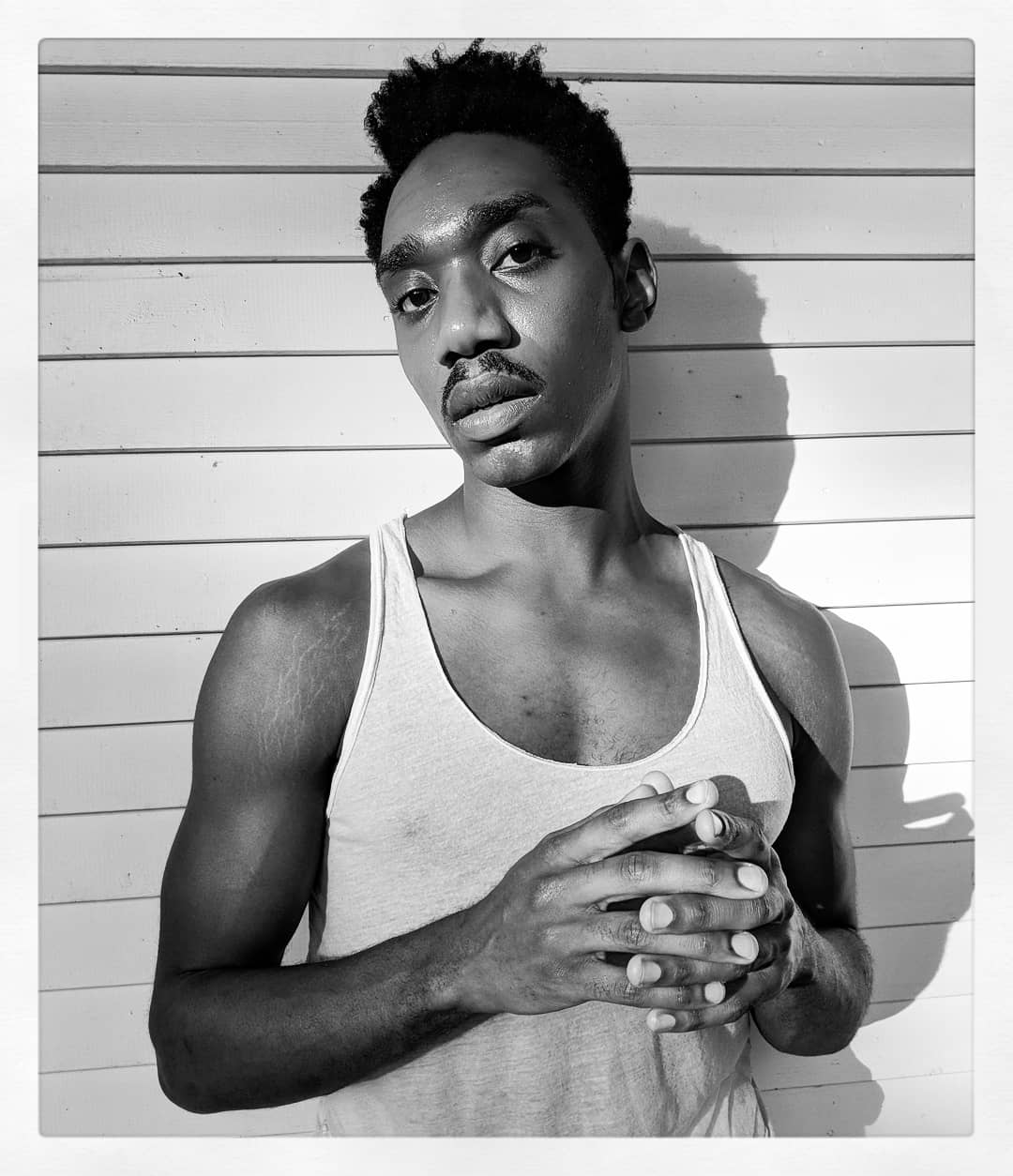

James, are you motivated? (Storytime)

- James Roberts

- Dec 17, 2020

- 3 min read

It’s hard to remember a moment from my childhood that brings me more joy than wearing my Adidas track spikes for the first time. They were a fiery red, accompanied by breathable white mesh and a set of three black diagonal lines along the side. They felt practically weightless, and made me feel legit the day I debuted them at practice. “Red Rider”, one of the older guys called me as we went through our warm-up series of toe walks, lunges, and high knees. Up until that point I’d felt all but invisible to the older runners, but on that day those red shoes made someone take notice. It felt good.

Since watching the Olympics, and a certain pair of golden spikes take center stage the previous Summer, track had become a full fledged obsession. I was sprinting up the stairs, long jumping down the hallway, and attempting to pole vault in the yard (don’t ask). I couldn’t wait to get back for the next season.

Sports had been a sore spot for a long time. As I’d grown up, I’d felt the not-so-subtle urgings of the men around me.

“Why he ain’t in football?”

“Don’t you want to play ball with the other boys?”

The short answer was “No”. My parents even enrolled me in a sports day-camp one summer. We spent a week learning all of the big team sports, and the only thing I enjoyed was lunch.

By then I’d gotten used to the looking, the pointing, the laughter, and the whispers of sissy and fa**ot aimed my way. Fumble a pass in one of their oh-so-precious touch football games and those whispers escalate. Quickly. The following summer, after that ill-fated sports camp, I tried track for the first time, and as the season went on something clicked. Finally, a sport where my success didn’t hinge upon interactions with borderline-abusive peers. My only obstacle was the clock.

I came back for my second season ready to make a real impression. However, without me realizing, something shifted in the intervening months between me and my peers. I couldn’t quite tell what it was until we were on the road, heading to our first out of town meet. As we traverse I-75 and near the arena, I hear this rhythmic, bassy call and response of: “Chris, are you motivated?”, followed by an emphatic “Hell yeah, I’m motivated!” being passed around the bus. I assume this is just the older guys getting themselves pumped up, and that I’ll be excluded from any of this commotion. However as the other boys my age are called in to participate, I begin sinking deeper and deeper into my sweaty brown faux leather seat, desperately trying to disappear. And then I hear it:

“James, are you motivated?”

Followed by a pause, an attempt, and a dismal failure.

The thing is that I actually am motivated! I want to get out there and kick ass like everyone else, but whatever it is I’m supposed to have that makes those words come out with any sort of conviction is not there. And though no one says it outright, it feels like I’ve dropped the ball.

Now that I’m super-sensitive and hyper-aware, over the next couple of days I begin to observe this performance of hyper-masculinity in which I, a sprinter no less, am expected to participate. Some aspects seem harmless, while others don’t sit well with me at all. “Maybe all sports are like this,” I say to myself, thinking fondly of the absolute lack of this kind of tension with other guys in the local boys choir I sing with. I finish out the season, but those fiery red spikes never touch my feet again.

Getting out of that particular environment was the only action I knew to take at the time. But what sucked about that decision is that I still loved track (still do). At 11 years old I lacked the skills to know that my presence was valid even if I didn’t fit that “hyper-masculine sprinter” mold that had been definitively burned into my mind by the likes of Michael Johnson, and Maurice Greene. It bothers me to this day, and I think it’s why I’m such an advocate for creating an affirming space in my yoga offerings. I never want anyone to feel pressure to give the performance of “ideal yoga practitioner”. Because like the “hyper-masculine sprinter” archetype, it’s all a show.

Comments